Epidural anesthesia is a widely used technique for pain relief. Although developments in the tools and technical skills of anesthesia providers have improved the safety and efficacy of epidural anesthesia, success can vary across cases. Some have proposed that the presence of an epidural septum may influence how local anesthetic spreads within the epidural space and account for some of the variability in the effectiveness of epidural anesthesia—however, this idea remains unsupported by current evidence.

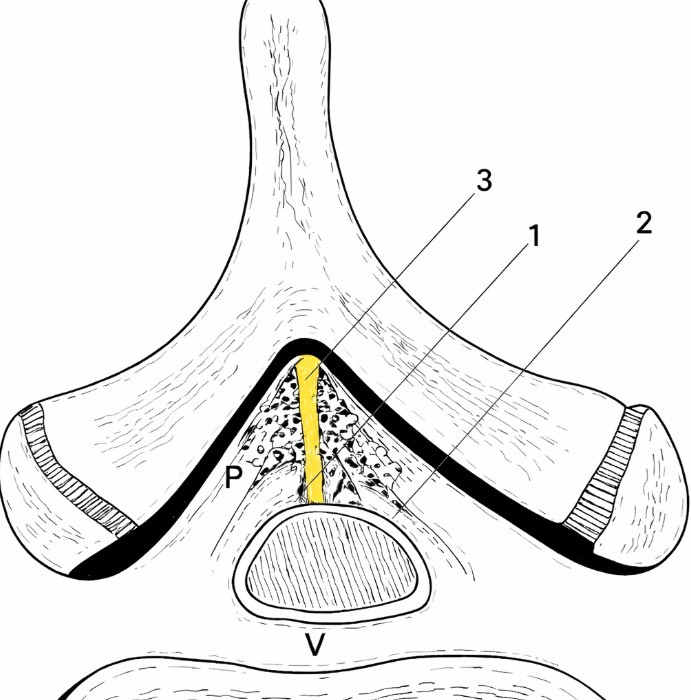

Medically, epidural anesthesia relies on the accurate placement of medication within the epidural space, which surrounds the spinal cord and nerve roots. This space contains fat, blood vessels, and connective tissue, all of which can influence how anesthetic agents spread. Variability in epidural anatomy has long been recognized as a factor in inconsistent or incomplete blocks 1,2.

The epidural septum refers to bands or partitions of connective tissue that may divide portions of the epidural space. These structures are thought to run in a midline or paramedian orientation and may limit the uniform spread of anesthetic solution. While described in anatomical studies and clinical observations, the presence and consistency of an epidural septum can vary significantly among individuals 1,2.

Anesthesiologists have noted that some patients experience patchy or unilateral epidural blocks despite a technically correct placement of the injection or catheter, potentially producing detrimental impacts on patient care. A proposed explanation is the existence of an anatomical barrier that restricts anesthetic flow to one side. These observations have driven interest in collecting evidence as to whether a septum within the epidural space contributes to variable clinical outcomes 3–5.

Imaging studies and cadaveric examinations have provided mixed evidence regarding the impact of an epidural septum on epidural anesthesia. Some findings suggest that connective tissue bands can influence local anesthetic spread, while others indicate that these structures are incomplete or flexible, rather than true partitions. This variability makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions with regard to their functional impact during routine epidural anesthesia 6–8.

If an epidural septum does affect anesthetic distribution, it may help explain why some epidurals require catheter adjustment, repositioning, or additional dosing. Clinicians often address uneven blocks by withdrawing or advancing the catheter, changing patient position, or administering supplemental medication. These practical strategies reflect an understanding that anatomical variation, including possible septations, can eventually influence outcomes 5,9,10.

At present, there remains no clear consensus that an epidural septum consistently alters the effectiveness of epidural anesthesia. Much of the evidence is indirect, based on small studies or clinical inference rather than large, definitive trials. As a result, the concept remains a plausible but not fully proven contributor to epidural variability.

The idea of an epidural septum highlights the complexity of epidural anatomy and its potential influence on anesthesia performance. While there is some evidence suggesting anatomical barriers within the epidural space may affect anesthetic spread in certain cases, current data do not support a uniform or predictable impact. Ongoing research and improved imaging techniques may further clarify whether an epidural septum plays a meaningful role in epidural anesthesia outcomes.

References

1. Epidural Space – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/epidural-space.

2. Epidural: What It Is, Side Effects, Risks & Procedure. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/21896-epidural.

3. Repeated Epidural Anesthesia and Incidence of Unilateral Epidural Block. https://openanesthesiajournal.com/VOLUME/13/PAGE/6/FULLTEXT/.

4. Finkel, J. C. The epidural dorsomedian septum as a possible cause for unilateral anaesthesia in an infant. Paediatr Anaesth 9, 456–459 (1999). DOI: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1999.00357.x

5. Hermanides, J., Hollmann, M. W., Stevens, M. F. & Lirk, P. Failed epidural: causes and management. British Journal of Anaesthesia 109, 144–154 (2012). DOI: 10.1093/bja/aes214

6. Guay, J. Epidural Anaesthesia: Images, Problems and Solutions. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie 59, (2012). DOI: 10.1007/s12630-012-9725-5

7. Srivastava, U., Pilendran, S., Dwivedi, Y. & Shukla, V. Radiographic evidence of unilateral epidural anesthesia. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 29, 571–572 (2013). DOI: 10.4103/0970-9185.119159

8. Al Nasser, B. Can we prove a septum existence of epidural space? Annales françaises d’anesthèsie et de rèanimation 22, 915–6 (2004). DOI: 10.1016/j.annfar.2003.09.013

9. Portnoy, D. & Vadhera, R. B. Mechanisms and management of an incomplete epidural block for cesarean section. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 21, 39–57 (2003). DOI: 10.1016/s0889-8537(02)00055-x

10. Failing Epidural Guideline. ESAIC https://esaic.org/failing-epidural-guideline/(2024).